What is the question all about?

In the exam you will be presented with one 8 mark question that asks you ‘How fully’ three different sources explain an issue in either the Athenian or Roman topic. Your job is to show you can interpret and explain information from multiple sources. You must also use your own knowledge to either expand further upon points in the source or identify significant omissions.

What marks are available?

You can be awarded up to 6 marks for interpreting and explaining points of content from the sources. You can be awarded up to 4 marks for further expanding upon ideas in the sources or for demonstrating wider knowledge by identifying omissions from the sources that further explain the issue.

If you only use one source from the three, then the maximum marks you can score is 4/8 no matter how good your identifying of omissions is. If you use at least two then you can still gain full marks (maximum of 3 marks per source)

What does the question look like?

Let’s walk you through an example question and I’ll show you how to answer one of these questions and I’ll make comments on my thinking as we go through it. Below is a typical example of what one of these questions looks like. This one relates to topic one of the Life in Classical Greece, Power and Freedom unit – Athenian democracy.

As you can see, there are three sources to interpret and explain the information from. One of these is a picture source of an archaeological object from ancient Greece or Rome and this will always be the case:

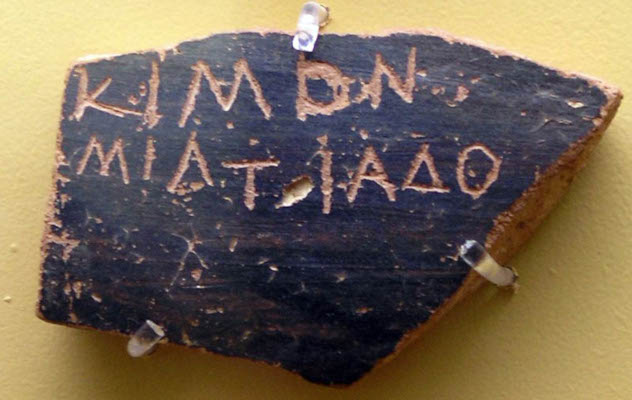

Source A shows an ostracon from 5th century BC Athens.

Source B is an extract from the memoirs of the Athenian writer Xenophon.

You are not shy with extremely clever people. Nor are you nervous of people who have a great deal of influence. And yet you don’t have the guts to speak in front of those who are the least clever and have no influence. Surely you aren’t too shy to meet cleaners and dyers, shoemakers, carpenters, farmers, merchants, market people? Well, these are the sort of people who make up the Assembly.

Source C is an extract from the histories of the Athenian politician Thucydides.

Our form of government is no copy of our neighbours’ laws. Far from imitating others, we are an example to them. Our form of government is called a democracy, that is, power in the hands of the whole people, not just a select few. When there are disputes between individuals, everyone is equal before the law. In public affairs, people are given a position because they deserve it: they get the job because of their own talent, not just because it is their turn. No one is kept out of the limelight just because he is poor, if he can be of some use to the city. We are tolerant in our personal relationships, and in public life we do not break the law, because it is the law that we fear.

How fully do Sources A, B and C explain the democratic system in 5th century BC Athens?

Use at least two of the sources and your own knowledge. 8

The blue highlighted question lets you know what you should focus your comments on. In this case they can focus quite broadly on the democratic system in Athens.

The text highlighted in pink is a reminder that you must use at least two of the sources and your own knowledge. It is worth remembering that if you only use two of the sources, you run the risk that when dealing with your omissions, they might have been mentioned in the unused source!

What do I do?

It’s good practise to divide your answer up into short paragraphs, one for each source and then one for your omissions. It makes your answer nice and clear for both you and the marker. You can deal with the sources in any order but I’m going to deal with them here in the order that they appear.

Step 1:

You must demonstrate what the SQA call process at the start of your answer and so the easiest way to do that is to make a simple statement using the question that shows you understand what you’re doing:

“The sources quite fully explain the democratic system in Athens but do not give the complete picture.”

Step 2:

I’m going to deal with the picture source first. The object should act as a “discussion point” for you to demonstrate what you know about how it fits within the topic. In this case we have an ostracon which as you’ll know was a voting token used in the process of ostracism. Given that ostracism was an important part of the democratic process, I’ll try and gain three marks by explaining what ostracism was and how it was part of the democratic process. Here goes:

“Source A shows an ostracon which was a broken piece of pottery upon which a citizen would scratch the name of the person he wished to see ostracised or banished from Athens. Citizens would decide each year in the Assembly if an ostracism was necessary and if it was, it took 6,000 votes in the voting pens of the Agora for it to be valid. Ostracism was used to banish a citizen for ten years and was thus an effective deterrent to any one citizen setting himself up as a tyrant as powerful men feared being brought down by the people. The banished person didn’t lose any of their property or suffer any other punishment, they simply had to leave unless recalled.”

As you can see from above, I’ve used a basic description of the ostracon’s function in the democratic system to lead into wider points on ostracism as part of the democratic system. These points are detailed, relevant and accurate and so would likely score three marks.

Step 3

Now I’m going to work on the two written sources. You can choose to paraphrase the source content and explain it or quote and explain it. I prefer quoting and explaining as it makes things very clear to a marker so below are the two sources with the parts I think I’m going to comment on in bold.

Source B is an extract from the memoirs of the Athenian writer Xenophon.

You are not shy with extremely clever people. Nor are you nervous of people who have a great deal of influence. And yet you don’t have the guts to speak in front of those who are the least clever and have no influence. Surely you aren’t too shy to meet cleaners and dyers, shoemakers, carpenters, farmers, merchants, market people? Well, these are the sort of people who make up the Assembly.

Source C is an extract from the histories of the Athenian politician Thucydides.

Our form of government is no copy of our neighbours’ laws. Far from imitating others, we are an example to them. Our form of government is called a democracy, that is, power in the hands of the whole people, not just a select few. When there are disputes between individuals, everyone is equal before the law. In public affairs, people are given a position because they deserve it: they get the job because of their own talent, not just because it is their turn. No one is kept out of the limelight just because he is poor, if he can be of some use to the city. We are tolerant in our personal relationships, and in public life we do not break the law, because it is the law that we fear.

I’ve highlighted the bits of the source I think are useful in bold. Here they are below:

And yet you don’t have the guts to speak in front of those who are the least clever and have no influence. Surely you aren’t too shy to meet cleaners and dyers, shoemakers, carpenters, farmers, merchants, market people?

Our form of government is called a democracy, that is, power in the hands of the whole people, not just a select few.

We do not break the law, because it is the law that we fear.

These are useful pieces from the sources that allow me to provide an explanation and expansion on how they help me to understand the Athenians democratic system. I’m going to use what we’ve learned about the democratic system to make these comments. As I’ve said, you can either use the quotes and then explain their usefulness or paraphrase the source and explain. They’re both fine as long as you aren’t simply stating what the source says. You must interpret and explain the quotes:

“Source B states ‘And yet you don’t have the guts to speak in front of those who are the least clever and have no influence. Surely you aren’t too shy to meet cleaners and dyers, shoemakers, carpenters, farmers, merchants, market people?’ This is in reference to the fact that any citizen who attended the Assembly could speak their mind openly and yet to do so was a nerve-wracking experience that men would have needed training and confidence to become comfortable with. It also shows the highly diverse make-up of the Assembly as it was populated by ordinary citizens with common trades as there was no wealth qualification for citizenship in Athens and so laws passed in the Assembly were passed by those who would be bound by them.

Source C states that ‘Our form of government is called a democracy, that is, power in the hands of the whole people, not just a select few’ which is correct insofar as the citizens directly governed themselves, however it is slightly misleading in that women, foreign born metics and slaves had no political power so power was not in the hands of the whole people, just the citizens. It also claims that ‘We do not break the law, because it is the law that we fear’ which is a clear reference to the fact that Athenians were not judged by kings and tyrants but by themselves – they passed the laws and when they were broken, individuals would prosecute each other in a court where a randomly selected jury of citizens would decide their guilt.”

These are some good points because they go beyond simply telling us what the source says and the comments interpret the points in the source and explain how they shed light on the democratic system. When combined with our response to Source A, there is more than enough here to get our 6 marks for interpreting the sources.

Notice that I’m not referring to the usefulness of the source. Many people get confused between evaluate the usefulness and how fully questions and try to answer them in the same way. You don’t have to get into who wrote the source, when, bias etc etc in a how fully question. If you do, you’re wasting exam time and thus potential marks!

Step 4

Now having interpreted the content of the three sources, I’m going to explain a few points about the democratic system that are not mentioned in the sources in order to access the marks that are awarded for pointing out omissions. None of the sources mention, for example, the Boule or Council of 500, the appointment of archons, the election of generals, the use of random lot, the rights and responsibilities of citizens. I’m going to pick a couple of these points to expand upon below. Here goes:

“However, none of the sources mention the existence of the Boule which was a council whose job was to ensure the smooth day to day running of Athens by meeting foreign dignitaries, setting the agenda for meetings of the Assembly, chairing those meetings and ensuring its will was carried out. The Boule consisted of 500 men who were over the age of thirty with 50 being chosen from across Athens’ ten tribes by random lot to serve for the year. A different group of fifty, or prytaneis would serve each month and their competence would depend upon chance as their initial selection was random. None of the sources make reference to specific positions which were elected such as generals as it was sensibly believed that these important positions should be filled by skilled individuals rather than random chance.”

These points are detailed, accurate and relevant in explaining the Athenian democratic system and so would take us up to our full 8 marks.

So our full answer would look like this:

“The sources quite fully explain the democratic system in Athens but do not give the complete picture. Source A shows an ostracon which was a broken piece of pottery upon which a citizen would scratch the name of the person he wished to see ostracised or banished from Athens. Citizens would decide each year in the Assembly if an ostracism was necessary and if it was, it took 6,000 votes in the voting pens of the Agora for it to be valid. Ostracism was used to banish a citizen for ten years and was thus an effective deterrent to any one citizen setting himself up as a tyrant as powerful men feared being brought down by the people. The banished person didn’t lose any of their property or suffer any other punishment, they simply had to leave unless recalled.

Source B states ‘And yet you don’t have the guts to speak in front of those who are the least clever and have no influence. Surely you aren’t too shy to meet cleaners and dyers, shoemakers, carpenters, farmers, merchants, market people?’ This is in reference to the fact that any citizen who attended the Assembly could speak their mind openly and yet to do so was a nerve-wracking experience that men would have needed training and confidence to become comfortable with. It also shows the highly diverse make-up of the Assembly as it was populated by ordinary citizens with common trades as there was no wealth qualification for citizenship in Athens and so laws passed in the Assembly were passed by those who would be bound by them.

Source C states that ‘Our form of government is called a democracy, that is, power in the hands of the whole people, not just a select few’ which is correct insofar as the citizens directly governed themselves however it is slightly misleading in that women, foreign born metics and slaves had no political power so power was not in the hands of the whole people, just the citizens. It also claims that ‘We do not break the law, because it is the law that we fear’ which is a clear reference to the fact that Athenians were not judged by kings and tyrants but by themselves – they passed the laws and when they were broken, individuals would prosecute each other in a court where a randomly selected jury of citizens would decide their guilt.

However, none of the sources mention the existence of the Boule which was a council whose job was to ensure the smooth day to day running of Athens by meeting foreign dignitaries, setting the agenda for meeting of the Assembly, chairing those meetings and ensuring its will was carried out. The Boule consisted of 500 men who were over the age of thirty with 50 being chosen from across Athens’ ten tribes by random lot to serve for the year. A different group of fifty, or prytaneis would serve each month and their competence would depend upon chance as their initial selection was random. None of the sources make reference to specific positions which were elected such as generals as it was sensibly believed that these important positions should be filled by skilled individuals rather than random chance.”