Although Roman colonisation was forceful and unconsensual, becoming part of the Empire wasn’t entirely disadvantageous for natives of the colonies and the quality of life of these people often improved. Rome had a reason to treat its provinces well, because this was the best way to ensure that rebellions wouldn’t break out. Therefore, Rome was relatively tolerant towards the people within Roman provinces, and often allowed them to continue their ancient traditions even after they became Roman subjects.

However, Rome also had an interest in promoting romanisation, the process of making people in the provinces more similar to those who lived in Rome. This involved building key Roman infrastructure such as aqueducts, bath houses and amphitheatres, and making people from the provinces worship Roman gods. This allowed a greater deal of cohesion between Rome and her provinces, ensuring that discrimination and unrest between different areas of the Empire would be less likely to occur. It also made administration of things like taxes easier, because the system was the same throughout the Empire, and meant that Romans choosing to live in a province far away from Rome would feel more at home.

Therefore, the administration of Roman provinces was a compromise between Romanisation and allowing natives to keep their old culture and systems of government. The degree to which a province was romanised varied greatly. As soon as a territory was conquered and became a province, one of the first things the senate would decide was how much self-government it would be given, i.e. to what extent Romans would be in charge of the province, and to what extent the people within the province would be in charge of their own affairs.

Many provinces were allowed to keep some autonomy in governing their people. For example, when Rome colonised Spain it had a tribal society, and these tribes remained an important body within the government of the province. Taxes were collected by tribe in Spain, and cases could be taken to pre-colonisation tribal courts. A similar attitude could be seen in many other provinces, where locals who had been in positions of power before Rome invaded were allowed to remain there once their community became governed by the Romans. Furthermore, some particular cities within a province were sometimes allowed to self-govern to a much greater extent than the rest of the Empire.

Why was it a good idea for Rome to allow its provinces to keep some of their culture and government?

Why was it a good idea to Romanise the provinces?

What were the advantages to allowing provinces to govern themselves differently? What were the disadvantages?

Every province was controlled by a governor. This governor essentially made all of the decisions in the province, and can be compared to modern Britain’s local MPs. Every consul and praetor who had just finished his time in office was eligible to become a governor, and who got what province was decided by the Senate. Governors typically served for a year but this could be extended.

A governor had many important roles. For example, he supervised enactment of Roman laws: he oversaw courts to ensure that they were fair. One of his other key jobs was to control and direct the Roman troops that were stationed in his province, and fight any battles (e.g. against anti-Roman rebels) that were necessary within his province. He was in charge of collecting taxes from the inhabitants of a province and giving them to Rome. Therefore, the governor had control of arguable the three most powerful aspects of any nation: the law, the military, and the finances.

In addition to this, a governor ensured that all public needs were met. This included the building of aqueducts, bridges, roads, temples, amphitheatres, etc. He therefore played an essential role in the romanisation of the provincials.

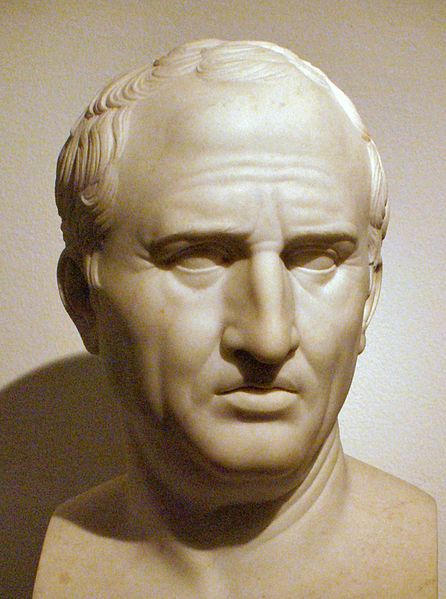

Governors varied drastically in competence and quality. There were many good governors, one of the best examples of these being the politician Cicero. Cicero was (rather unwillingly on his part) given governorship of the province Cilicia. His predecessor Appius was a classic bad governor, as he had negligently allowed the number of Roman troops stationed in the province to decrease and turned a blind eye to the illegal activities of businessmen and moneylenders so that he could profit. Cicero, according to what he wrote, completely turned this situation around. Firstly, he recovered the lost forces and began a campaign against the bandits plaguing the province and extorting the natives. He then cracked down on illegal business activity.

One of Cicero’s key strengths as a governor was that he didn’t always try to force his authority on the provincials. He travelled round his province to listen to the views of the people, and tried to allow them to have as much independence in governing themselves as possible.

Perhaps most importantly, Cicero didn’t seem to be motivated by making money from his province. He was unwilling to extort the people, and didn't inflate their taxes so that he could get his own cut. He lived comparatively frugally, and even returned his unspent living allowance to the senate.

On the other hand, it is certainly true that the majority of governors, particularly in the late Empire, were corrupt, and only became a governor to make money. There were few more ambitious than Verres, who managed to extort 40 million sesterces from the people living in his province, Sicily. The Sicilians were so offended by this that they took him to the court established in 149 BCE to punish corrupt governors. They chose Cicero himself to represent them, and he fought his case well despite many setbacks caused by the power of Verres’s money and the intervention of his influential friends. Eventually, the tide completely turned in Cicero’s favour and Verres knew his best and only option was to go into voluntary exile. This tale of corruption has a just ending, but remember that most others did not.

There are many reasons why governors were often corrupt. Governors were politicians who had just served as a consul or praetor, and the election campaigns needed to become a consul or praetor were often incredibly expensive. Therefore, many new governors were very poor when they assumed office, and some had even taken out massive loans in order to finance their political activities. Furthermore, a governor had very little oversight from superiors in Rome during his time in office. He was technically answerable to the senate and the consuls - the senate could even punish him if he didn’t do a very good job - however the reality was that he was geographically very far away from anyone who could stop his actions. The only way for him to communicate with the senate was by messenger, which meant that any communication between Rome and the provinces was very slow and intermittent. So, in practice a governor could largely do what he wanted while in office.

In summary, governors were politicians who were usually in a bad economic situation and didn’t have very much scrutiny from superiors. They weren’t paid for the work they did as governors, so couldn’t earn money this way. Therefore, it seems quite obvious that many would turn to corruption. As the Empire developed, it became more common for governors to treat their province primarily as a money-making enterprise.

Corruption became so pervasive and blatant by 149 BCE that a court for trying ex-governors was established. However, there were many issues with this system. The jury was made up of ex-senators who either had already been governors or wanted to be governors, so these people were usually unwilling to punish one of their own. The ex-governor was usually much richer than the provincials complaining about him, so he could spend more money on expensive character witnesses, lawyers, speech writers etc. Verres was one of the few ex-governors who was, in a certain sense, punished by the court, although he fled Rome before his sentence passed. Even in his case, when it was so obvious that he had committed fraud, Cicero faced many challenges in convincing the jury because of the power of Verres’s money and his influential friends.

Most of the expenses of the trial were paid for by the complainant, which dissuaded many potential complainants from bringing a case to the court. Verres was only brought to court because of the sheer amount he defrauded the Sicilians – other smaller or less obvious acts of corruption would likely not have made it to court. Governors that were still in office couldn’t be tried, so complainants had to wait until after their term had ended to make a complaint. Therefore, provincials had no power to control their governor until after the governor had retired, at which time there was little point in bringing forward the case because the governor had already done all the harm he could to the people. Even so, the threat of being taken to court may have prevented some governors from the most blatant and arrogant acts of corruption.

If you had been tasked to solve this problem, what reforms would you have made to reduce the corruption among governors?

Using Cicero as an example, what are the qualities a man had to have to be a good governor?

Using Verres as an example, what are the qualities a man had to have to be a bad governor?

Why was the court that tried governors flawed? How could this system have been improved?

Because Romans often maintained a province's pre-colonisation system of taxation, systems of taxation differed quite significantly throughout the Empire. This made tax collection quite confusing and difficult to understand.

There were two common methods of taxation. The first was a stipendium, an annual payment of a fixed amount of money or goods. It was easy to pay and collect this, because the amount had already been agreed and always stayed the same. A stipendium was usually collected by a quaestor. Provincials who paid this type of tax were usually less likely to be victims of extortion. On the other hand, since the amount paid in a stipendium always stayed the same no matter whether the harvest that year was good or bad, a provincial could be forced to pay a large amount even when they didn't make much money from their harvest.

The other type of taxation was a decuma, money or goods worth 10% of the annual harvest of that year. This was much more difficult to collect, because the total worth of the harvest had to be decided and then the amount of tax had to be calculated. A decuma was collected by so-called “tax-farmers”: rich businessmen who bid for a contract to collect the taxes – the highest bidder won. The winning tax-farmer would pay however much they had bid to the Roman treasury, then keep whatever they collected in taxes. This system meant that tax-farmers had an incentive to extort the taxpayers, since the more money they extorted the larger profit they would make. This was particularly true during years when crop harvests were bad: if the decuma was so small that it was less than what the tax-farmer had paid to get the contract, the tax-farmer would be making a loss and so would be incentivised to make up for this through extortion. Governors often allied with tax-farmers so that they, too, could make more money. This meant provincials were usually unable to ask for their governor’s help if they were being extorted.

To make the system even more complicated, the residents of some cities were free from paying taxes, because the Roman government decreed that it would be so. It should be noted that while most of the collected tax went back to Rome, some of it was used to pay for the governor’s living expenses and other costs associated with running the province.

Would you have rather paid a stipendium or a decuma? Why?

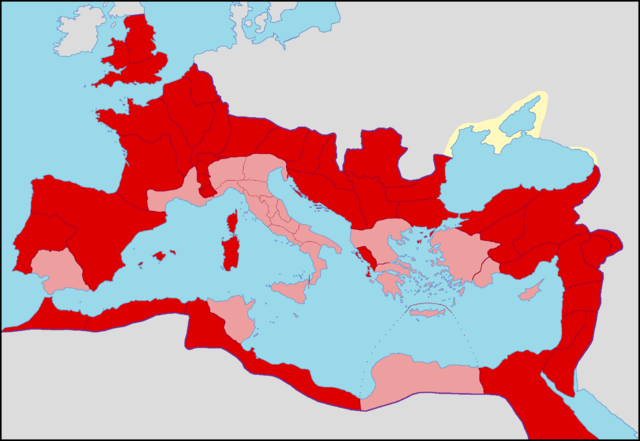

Most of the above information concerns the Roman provinces while Rome was still a democratic Republic. There were some changes to how provinces were ran after Rome had an Emperor. During the Roman Empire, provinces were split into two types: Imperial Provinces and Senatorial Provinces. However, provinces could change from senatorial to imperial or vice versa, depending on what the situation demanded.

Senatorial provinces were more stable: they had usually been part of the Empire for a long time, tended not to be close to the borders of the Empire and faced little possibility of rebellion or invasion. Therefore, there was less of a strong military presence needed. Senatorial provinces were governed in a similar way to provinces during the Republic: the governor was usually an ex-consul or praetor and usually stayed in office for a year. The provincials' tax was collected by a quaestor. The major distinction was that the ex-consul or praetor governing the province no longer had control of the military – this right was reserved for the Emperor.

Imperial provinces were the opposite: they were regarded as dangerous and needed a strong military presence. The Emperor was directly in charge of these provinces, but since he had to stay in Rome he appointed commanders to lead the provincial troops in his stead. As well as presiding over military affairs, this commander became the governor of all other matters within the province. Procurators were appointed by the Emperor to collect taxes from imperial provinces. Examples of imperial provinces include Britannia and Syria.

Sometimes the emperor gave people, or even entire cities, the right of citizenship. No one in any of the provinces was born a Roman citizen, so this was a very big deal. Citizenship could improve a man’s life because it allowed him to appeal to the Emperor when there was a legal dispute, and he could become a government official. This gave him a much greater deal of legal and political power. Because citizenship was highly sought after by many provincials, the emperor could use giving certain people or cities citizenship to appease the people and ensure their loyalty to Rome didn’t waver.

The system of taxation was significantly changed by Augustus, the first Emperor of Rome. Under his decree, there were now three major types of taxes: direct taxes were levied on physical property such as houses or land, and poll taxes included property that wasn’t a physical entity, i.e. a business or the sale of items. Then, indirect tax was levied on slave manumission, inheritance or certain goods being transported between different area (similar to the modern day customs tax). Taxes didn’t necessarily have to be paid in cash; the same value could also be paid in certain goods such as grain.

Everyone in the Roman Empire apart from Italians had to pay tax. The only exceptions to this rule were the colonies established throughout the empire by Caesar and Augustus.

Overall, the taxation system during the empire was much fairer than during the republic. In a senatorial province, a quaestor was in charge of collecting taxes, and he was usually an experienced official who wanted to find favour with the emperor for doing a good job, so would have an incentive to be competent and honest. He could use tax-farmers to collect indirect taxes, but kept them under a much greater degree of scrutiny so that they wouldn’t be able to embezzle. In imperial provinces, taxes were collected by a procurator who had been assigned by the emperor. He was also keen to do a good job to please the emperor. Furthermore, because he was appointed directly by the emperor he was largely independent of the governor, so could serve to keep a check on the governor and ensure that he did his job well.

The governor had no role to play in tax collection, so he had no motive to aid in the extortion of provincials because he couldn’t profit from it. Therefore, he became another check on tax collectors so that they did their job well. Furthermore, after Rome became an Empire it was hard to avoid paying tax due to officials keeping a much closer eye on population statistics.

Aside from this, one of the major reasons why governance of the provinces was more successful after Rome became an Empire was that there was a much better communication network than during the republic. The courier service meant that messages could be sent much faster and more reliably than before. Governors were now more accountable to the Emperor in Rome, because he was able to find out what was happening in a province much faster. The courier service also allowed governors to question the emperor about what they should do in certain situations. After Rome became an empire, governors had more checks and balances to stop them from participating in corruption, and power was centered more greatly in Rome.

Finally, governors were given a regular salary during the empire. This meant governors were less likely to engage in corruption because they already had a legal source of income.

What were the major differences between senatorial and imperial provinces?

Why was government of provinces better under imperial rule?

What, in your opinion, was the most significant improvement?

Some kingdoms didn’t immediately become part of the Roman Empire – instead, they became client kingdoms. Client Kingdoms weren’t officially ruled by Rome and could have their own independent king or prince, however they were expected to only make the decisions Rome wanted them to. If Rome didn’t have an opinion, they could make the decision themselves. The relationship between Rome and a client kingdom was similar to the patron-client system.

Client kingdoms were beneficial to Rome because they provided a buffer zone between the Empire and the anti-Roman societies surrounding it, protecting the Empire and making it less liable to revolt. However, client kingdoms typically did not last very long: eventually, they became incorporated into the Empire because they tried to rebel against the Romans or because a King or Prince left their state to Rome in his will. Therefore, though client kingdoms may have seemed a half-way house between being a province of Rome and a free nation, in reality they were already on the slippery slope to becoming completely under the control of the Romans.

What were the benefits of client kingdoms to the Romans?

Can you think of any potential benefits of being a client kingdom for the kingdoms themselves?

Rome had a massive cultural impact on its colonies through its process of romanisation. This had both positive and negative consequences for the provincials.

One key piece of Roman culture that was brought to the provinces was the bathhouse. This was a public bath supplied with water from a nearby stream or aqueduct, heated by log fires. These bath houses not only improved the sanitation of the provincials (therefore helping to prevent the spread of disease), they also served as a cultural meeting place to socialise and form friendships. They could be regarded as a form of entertainment, because people could spend a long time in a bathhouse having discussions with friends.

Since most bathhouses weren’t near natural sources of water, they were dependent on another Roman innovation, the aqueduct. As well as sourcing bathhouses, aqueducts also provided water for drinking, cleaning dishes, washing clothes, etc. They provided a source of clean water directly to the provincials – before the aqueducts, these people would often have had to treck for miles to get water, and this water would often be dirty and contaminated. Therefore, aqueducts were time-saving and convenient, and they also helped to prevent the spread of water-borne disease.

Aqueducts were used for commercial as well as domestic use: they could be used in agriculture (by providing water to crops) or mining. Water was used in a process known as hydraulic mining, where it exposed the ore by hushing. Hushing involves directing a torrent of water towards an area of the mine, after which veins of metal ore would be revealed.

Water from aqueducts could also be used to power machines that refined and processed the metal that had been mined. Therefore, aqueducts helped turn the provinces into economically viable areas, allowing the people to prosper.

Sources of Roman entertainment such as ampitheatres and theatres were built, allowing provincials to experience Roman plays and gladiator fights. This would probably have been a more flashy and exciting form of entertainment than most provincials had experienced before, and allowed them more options as to what to do with their free time.

Romans built roads throughout the empire because it allowed them to move their military to different locations faster. These roads were paved, straight, and so well-engineered that many survive and are used today. Faster transport of the Roman military ensured that provincials would be better protected from invasion. Of course, it also meant that any rebellion started by unhappy provincials would be more likely to fail.

Roads not only allowed the faster transportation of troops, but also the faster movement of ordinary people to different parts of the empire. This encouraged trade, since traders could travel faster to different cities to buy and sell goods. Therefore, provincials could use things like olive oil and wine that they never would have access to otherwise. This was particularly true for provincials living in colder climates, such as Britons, who would not have been able to grow olives and grapes and so couldn’t have enjoyed olive oil and wine were it not for trade. Furthermore, trade boosted the economy of provinces, since local producers could sell their goods to a much larger and more international audience.

However, romanisation didn’t always have a positive impact. The Roman governor of a province was responsible for crime and punishment in that area, so citizens had to obey Roman laws. A province’s local laws and customs could be entirely overlooked in favour of Rome’s. This must have been frustrating and humiliating for provincials who had practiced the same laws for centuries prior to invasion. They lost part of their culture due to Roman rule. On the other hand, many Roman governors were quite lenient in this regard, and allowed their provincials to practice native laws and be tried in traditional tribal courts as long as this didn’t interfere with Roman interests.

How Rome treated a provincial's religion depended very much on what type of religion they practiced. Polytheistic religions (religions worshipping more than one god) were usually treated fairly leniently. They could worship their own gods as long as they worshipped Rome’s gods as well. In fact, native gods were often adopted into the medley of gods Romans already worshipped, and were associated with the Roman god that most resembled them. For example, in Bath the native goddess Sulis was linked to the Roman goddess Minerva because both had associations with healing. Therefore, native gods were usually worshipped alongside Roman gods and provincials could maintain this part of their culture even while part of the empire.

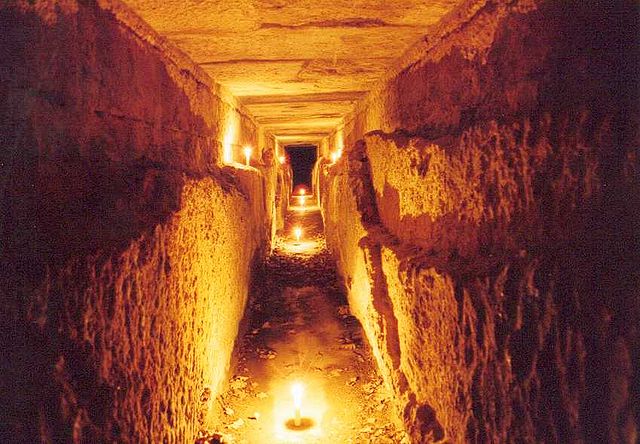

However, practionioners of monotheistic religions (religions worshipping only one god) such as Christians and Jews faced a very different fate. Because they tended to be unwilling to worship Roman gods as well as their own god (they believed that their god was the one true god and that worshipping any other would be heresy), they were often victimised and discriminated against within the empire. For example, some Christians were covered in wax and turned into human candles for Emperor Nero’s personal amusement. The main reason why monotheistic religions had such a hard time under Roman rule was that they refused to worship Roman gods. The Roman religious system included the belief that an emperor’s authority was given to them by the gods, and by refusing to believe in Roman gods it was felt that those practicing monotheistic religions were questioning an emperor’s legitimacy. They could therefore be viewed as potentially revolutionary and very dangerous.

The Latin language was spread throughout the empire. Most languages native to the provinces, unlike latin, were oral (they didn’t have a writing system and couldn’t be written down). This meant that anyone who had aspirations to gain power by becoming an official had to know Latin. It is unknown to what extent Latin replaced native languages, because it is quite likely that provincials still spoke their native language to one another when not engaged in official business. Furthermore, Latin had a hard time replacing Greek, a language that did have a writing system and also had a great and impressive history of influential scholars, writers and artists behind it. Particularly in the east of the Empire, Greek remained more dominant than Latin.

Why were aqueducts important?

What, in your opinion, was the most important impact of Roman roads?

Given that most native languages couldn’t be written down, why might it be difficult for historians to discover how much these languages were used in the daily lives of provincials?

In your opinion, what was Rome’s most important cultural impact?

There were many advantages to living under Roman rule. One of the most significant was the so-called Pax Romana, or Roman peace. With such a competent and large army to protect them, most provinces experienced relative peace, whereas without the Romans these communities would have been much more vulnerable to bandits, invasions and infighting. The peace that the Romans brought allowed provincials to focus on things other than how to protect themselves. On the other hand, the fact that Rome had such a strong military meant there was no doubt who was in control – provincial rebellions would be quickly put down.

The quality of life of provincials living under Roman rule was typically quite good. Innovations such as aqueducts improved sanitation, provided a convenient supply of water to the people and facilitated more efficient mining techniques. Bathhouses minimised the spread of disease and ensured that provincials lead cleaner lives, while also providing a hub for socialisation and entertainment. Amphitheatres and theatres provided entertainment for the masses, and gave provincials more options regarding what to do in their free time. However, although this romanisation can be said to have improved the quality of life of the provincials, it also meant they lost parts of their own cultural identity. Native customs were often lost.

Roads allowed the military to travel faster so that provincials would be better protected, however they also meant that troops could move to put down rebellions against unfair treatment faster. Roads increased trade, so that provincials could experience a wide variety of goods from throughout the Empire. Increased trade stimulated the economy, which made many provincials financially better off.

The fact that Romans melted down native currencies and introduced their own coinage throughout the empire also stimulated the economy, because a common currency made trade easier between different parts of the empire. However, a society’s coinage was part of their shared cultural identity, and this was lost when the common currency was introduced.

Latin may have replaced many native languages across the Empire. This made communication between officials easier because everyone who wanted any political power had to know the same language. It would have been impossible to run an Empire when members of the same administration couldn’t understand one another. The spread of Latin as a common language also made travel throughout the empire easier, because someone wouldn't have to learn a new language in order to survive in a different province. However, a community's language is an important part of their culture and shared identity, and this was lost due to Roman invasion. On the other hand, it is hard to determine to what extent Latin did replace native languages, and it is entirely possible provincials continued to speak their native languages in unofficial contexts.

Provincials had to follow Roman laws and systems of punishment. This emphasised Rome’s control over their lives, reducing their feelings of freedom and autonomy. However, many Roman governors allowed native laws and legal systems to continue in much the same way as they did before Roman occupation. This was the same for systems of government – governors often allowed people who had been in positions of power in their society before Rome invaded to continue to make decisions for their people as long as they didn’t interfere with Roman interests. Therefore, the provinces were sometimes allowed a certain amount of autonomy.

Provincials had to pay taxes even though Italians didn’t have to, and this was certainly unfair. Furthermore, during the republican period most provincials didn’t have citizenship and couldn’t vote in Roman elections. So, they had little say in who made the decisions in Rome. Of course, this didn’t matter during the imperial period, since no one could vote for or elect an emperor.

Romans allowed provincials to worship their own gods, as long as they worshipped Roman gods too. This was a compromise, and allowed provincials to continue their native religions. However, it can of course be argued that forcing provincials to worship Roman gods alongside their own was unfair. Furthermore, when worshippers of certain religions refused to accept the Roman religion, as was the case with Christians and Jews, they were persecuted mercilessly.

Particularly during the republican period, provincials could be extorted by tax-farmers and governors, and end up in poverty because of this. Governors in the republican period had no one to watch over them, so they could essentially do what they wanted to the provincials. There were courts to try governors for corruption, however they usually judged heavily in favour of the governor because the governor could use money to bribe the jury and buy the best lawyers and witnesses. All of the financial burden of the case was usually placed on the shoulders of the complainants, so not many cases were brought to trial. Only ex-governors could be tried, so provincials facing the tyranny of a governor could do nothing but wait for his time in office to end.

Governors usually changed yearly, so that if a governor was bad or corrupt provincials only had to wait a relatively short time before getting a replacement. On the other hand, this meant that there was no stability in government and long-term policies could usually not be put into place. Good governors were also not in office for very long before they were replaced.

At the end of the day, provincials usually had very little freedom to decide what would happen to them. They couldn’t decide how they were governed, who they were at war with, who their allies were, what their laws were and how criminals were punished, etc. This was likely very frustrating and disempowering for many provincials.

Do you think it would be more important to have Roman innovations or to keep your own cultural identity?

Would you rather have lived in a province under Roman rule, or outside Roman control?