While you won’t need to know most of the above video for your exam, it’s a good introduction to the section.

The initials “SPQR” were used frequently in Ancient Rome. For example, we can find them on Ancient Roman coins and monuments. SPQR stands for Senatus Populusque Romanus, which translates as “the Senate and the people of Rome”. This term was used to describe those who, in theory, governed the empire: the Senate, who had a lot of political power, and the people, who elected them into office. Therefore, SPQR was a motto for Roman democracy.

Answer this question after you have studied the rest of this section. Do you think the idea that the Roman Republic was governed by the Senate and the people was accurate?

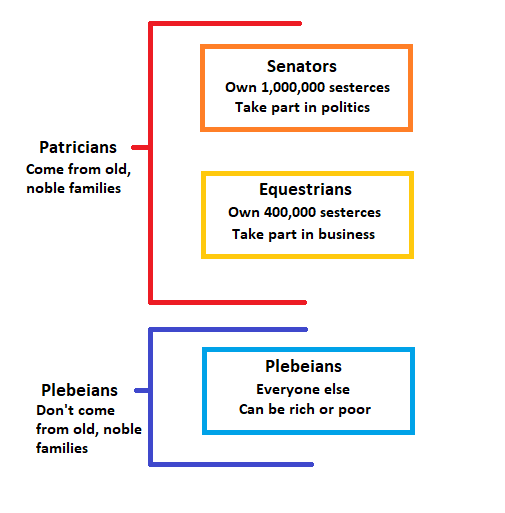

There were three distinct social classes in the Roman Republic. The highest group was the senators. Unlike in modern America, where the term "senators" is used to describe current members of the Senate, in Ancient Rome it referred to a social class determined by wealth. Therefore, not every senator was necessarily a member of the senate. However, only senators could be elected into the senate. Because they held a political role, they weren’t allowed to engage in business in order to prevent corruption. Therefore, they usually made their money through land-owning instead. A man needed to own 1,000,000 sesterces in order to qualify as a senator. Sesterces were an Ancient Roman currency, comparable to the British Pound Sterling. Although it’s very difficult to make direct comparisons between Ancient Roman and modern day currency, it’s estimated that an average Roman man could earn about 3-4 sesterces every day. So, we can see that to be a senator one had to be massively wealthy.

Equestrians were the next social group down, only slightly below senators. Instead of being politicians, equestrians engaged in business – this was how they made their money. They also did much of the essential work that allowed the smooth running of the empire. A man needed 400,000 sesterces to qualify as an equestrian.

Both the senators and the equestrians were patricians. Patricians were the nobles of Ancient Roman society. They came from prominent and wealthy families and could trace their lineage back to the early days of Rome.

Those who weren’t patricians were plebeians. These people didn’t have well-known, ancient family lineages. They didn’t have as many economic, political and religious rights as patricians, and rarely engaged in politics to a great extent. They filled their free time with entertainment such as gladiator shows. Around 200,000 plebeians qualified for the corn dole, a mix of grains given to the poorest in the Republic in order to prevent their starvation. However, many plebeians had enough money to live comfortably, and worked as labourers, tradesmen and small farmers. Some plebeians had great success as businessmen and became very rich. Although we get the modern word “pleb” from plebeians, in Ancient Rome plebeians could be well-educated and rich. The only qualification for someone to be a plebeian was that their family lineage wasn’t ancient and well-known.

Patricians and plebeians had different roles in areas of Ancient Roman society such as politics, religion, law, marriage, employment and the military. Patricians (in particular, the senators) had most of the political power in the Roman Republic – they were elected as all major officials.

All religious power was also in the hands of the patricians. Patricians were elected as all of the major religious officials. They also had control over the two major colleges of priests – the Augurs and the Pontiffs. Plebeians, on the other hand, were essentially banned from carrying out any important religious roles.

Patricians could essentially make up the law as it suited them, since Ancient Roman laws weren’t written down and plebeians usually had very poor knowledge of the law. Therefore, patricians could punish plebeians however they wanted to, and plebeians couldn’t challenge their decisions.

Patricians couldn’t legally marry plebeians, and vice versa. Both social groups had separate marriage ceremonies. If a patrician did try to marry a plebeian, any children produced would automatically be classed as plebeians.

The economy was largely supported by equestrians, who made money by being tax collectors, bankers and engaging in business. They were also often involved in lucrative public contracts to build necessities such as aqueducts and roads. Senators, on the other hand, couldn’t involve themselves with these pursuits as they were primarily political entities. However, they made their money by loaning large amounts of land out to others, mainly plebeians. So, patricians had a large amount of control of the economy, and played leading roles in every element of it.

Both patricians and plebeians served in the army. However, patricians took most of the important positions. This was partially because those with more important roles in the army had more expensive equipment, and every member of the army had to pay for their own equipment. Poor plebeians couldn’t afford to play an important role in the army. Furthermore, while patricians could afford to maintain their farmland while they were away fighting (for example, because they could afford slaves to look after the farm in their absence), plebeians couldn’t afford to do so and this caused serious financial problems for them. While patricians could gain glory from war by serving in important positions within the army, war often caused poor plebeians to sink further into poverty. However, remember that some plebeians were very rich, even as rich as some patricians. These rich plebeians were in many ways equal to patricians in the military.

Plebeians were involved in a number of occupations: they often worked as tradesmen, craftsmen, businessmen, etc. The poorest plebeians were usually small farmers or relied on the corn dole to survive. As has been previously mentioned, some plebeians became as wealthy as patricians. This started to erode preexisting social structures, as wealthy plebeians began to resent their lack of other rights compared to equally wealthy patricians.

Would you rather have been a senator or an equestrian? Why?

What was the major difference between patricians and plebeians?

In what part of society could rich plebeians be most equal to patricians?

Briefly explain the roles of the three social classes: plebeians, equestrians and senators.

The patron-client system greatly affected the political and social climate of the Roman Republic. It involved a client, usually a poor plebeian, and a patron, usually a wealthy patrician. A patron gave their client land, legal protection and food rations (or sometimes cash). In return, the client supported their patron – they voted for them, fought under their authority during wars, paid them respect, and sometimes helped to raise funds for certain matters such as dowries. Therefore, this was a mutually beneficial relationship.

A patron-client relationship was recognised in law, and neither patrons nor clients could testify against one another. It should also be noted that later on, the patron-client system expanded to include the relationship between a freed slave and his master.

In your opinion, which side got the most out of the patron-client relationship – the patron or the client?

The senate was made up of 300 people, each of whom served in the senate for their entire life, unless they were found guilty of a serious crime such as treason. The senate was controlled by about 20 very influential and well-known families called the nobiles. These families kept their power by relying on their vast numbers of clients, who were obliged to vote for them.

It may first appear that the senate didn't have very much power. After all, their main job was to advise officials, and they couldn't make many decisions on their own. However, the political climate in Rome became more and more complex, and consuls, who were only in office for a year, didn’t have time to build up enough knowledge to make important political decisions competently. Because of this, they usually relied greatly on the advice of the senators, who could build up knowledge of the political situation because they were senators for life. Furthermore, most officials would later become senators, so it would do them no good to anger future colleagues by going against their recommendations. Therefore, the senate grew to become the major decision-making body in Rome, and had immense power.

Senators weren’t directly elected into office by the people. However, before 80 BCE they were selected by magistrates called consuls, who were themselves elected. After 80 BCE, when someone was elected as a quaestor they immediately became a member of the Senate. Therefore, the public did indirectly choose who became a member of the Senate.

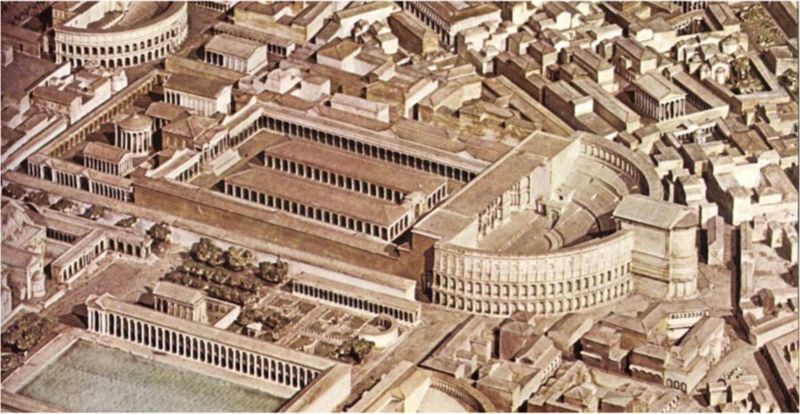

The senate had enormous power in a number of different areas. They handled any crises that the Roman Republic faced and chose who would govern Roman colonies. They also had a lot of control over the finances of the Republic, as they could allocate funds for the maintenance and construction of public buildings such as bath houses and amphitheatres, and make contracts with equestrians on behalf of the government to build public necessities such as roads. They couldn’t make laws by themselves, however they could pass decrees that advised other officials to do certain things, and these were usually obeyed due to the prestige and power of senators.

In many ways, having a Senate was beneficial for the Republic. The large number of people within the senate took absolute power away from one specific person. Many people had to agree for something to happen, reducing the possibility of one man staging a revolt and taking absolute power for himself.

The fact that there were a large number of senators allowed a good amount of debate and discussion – the best solutions are often found when many people critique other people’s suggestions, rather than one person making the decision by themselves.

Because senators served for life, they could build up the experience and wisdom needed to make the best choices for the nation. Most other Roman officials only served for comparatively short periods of time (usually about a year) and therefore couldn’t build up skill or knowledge. However, this meant senators had a massive amount of power, because they were the only people with the necessary experience to make the right decisions. Giving one group too much power was always dangerous, as they could use this power for their own benefit.

Another of the major issues was that senators were typically very wealthy patricians, who would often disregard the needs of the common people in order to fulfil the desires of other rich patricians. Furthermore, it was quite common for senators to be corrupt, and use their power for their own personal gain.

Although the Senate technically only had the power to advise magistrates, it is important to understand that in reality magistrates would almost always do what they said. There were a number of reasons why this was the case. We have already discussed the idea that the Senate had much more experience than individual magistrates, and in the very complex political environment of Rome, this experience was crucial to making the right decisions. So, magistrates were likely to listen to the advice of the Senate.

Also, magistrates were almost always members of the Senate. Quaestors, the lowest level of magistrate, automatically became senators after they were elected, and you couldn’t be an aedile, praetor, or consul without first being a quaestor. So, senators were magistrates’s colleagues, and they were more likely to listen to people of their social and economic class. It would do them no good to make enemies of the people they would be working with for the rest of their lives.

Senators, particularly the most influential ones, had a lot of political and military connections. Therefore, it would be a very bad idea to get on the bad side of senators by going against their advice. Many senators could make a life in politics very difficult for someone.

After magistrates had served for their full time, most wanted to become a governor of a province in the Roman Empire. Election campaigns were usually incredibly expensive, and being a magistrate was often very costly as well. This was particularly true for Aediles, who had to pay for festivals for the public. Being a governor, on the other hand, was a way to get much of this money back. Away from the scrutiny of other officials, governors could basically do what they wanted, and were often corrupt. They could also keep the spoils of any wars they fought in. Senators were in charge of appointing governors, so officials were often very keen to get on their good sides. This was another reason why magistrates would usually take the advice of senators.

What did senators have the power to do?

Overall, do you think the senate was good or bad for the Roman Republic?

Why did Senators have so much power over magistrates?

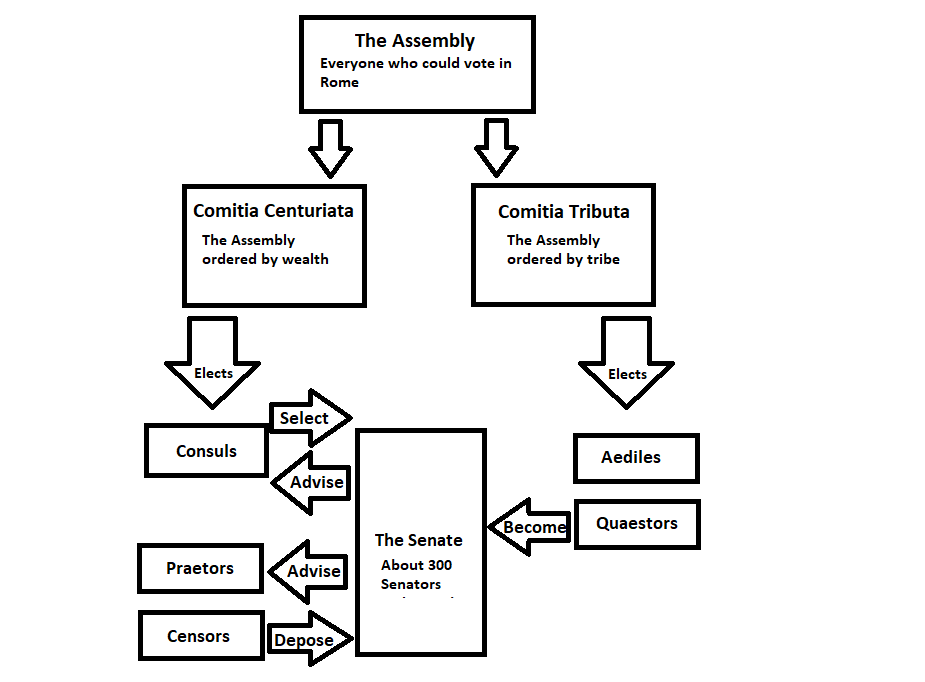

Roman citizens who were able to vote were collectively known as the assembly, or comitia in Latin. This comitia could be called and assembled by certain officials such as consuls. These meetings were called contiones, and were used by consuls to inform the people about something such as the specifics of a new law or a list of election candidates. No one voted during a contione; contiones were for people to receive information and debate on matters which they could vote on in the future. This was the only time in which the people were allowed to debate – they couldn’t debate when meeting as a comitia centuriata, comitia tributa, etc.

There were 4 types of assemblies, and each of these assemblies had a different purpose. These Assemblies included the same people – everyone eligible to vote in Rome – but they were organised differently. For example, the comitia centuriata was organised by wealth, and the comitia tributa was organised by which tribe you were part of.

Of the 4 assemblies, 2 were of only minor importance in the Roman Republic. These were the Comitia Curiata and the Concilium Plebis. In the Comitia Curiata, voters were organised into groups based on which family they were part of. The comitia curiata decided on some religious matters, and gave power to newly elected officials. However, this was only formal power – the comitia curiata didn’t elect officials, they only ceremonially handed over power to officials that had already been elected. In reality, the Comitia Curiata would never reject an official that had been elected.

The other minor assembly was the Concilium Plebis. This was the only assembly that went against the rule that all assemblies were made up of the same people – the Concilium Plebis, unlike all the other assemblies, didn’t include patricians. The Concilium Plebis was, as the name might suggest, only attended by plebeians. The main job of the Concilium Plebis was to elect the 10 Tribunes of the People every year.

The two major assemblies were the Comitia Centuriata and the Comitia Tributa. These are the most important assemblies for you to remember, and are described below.

What was the purpose of contiones?

Do you think contiones were important?

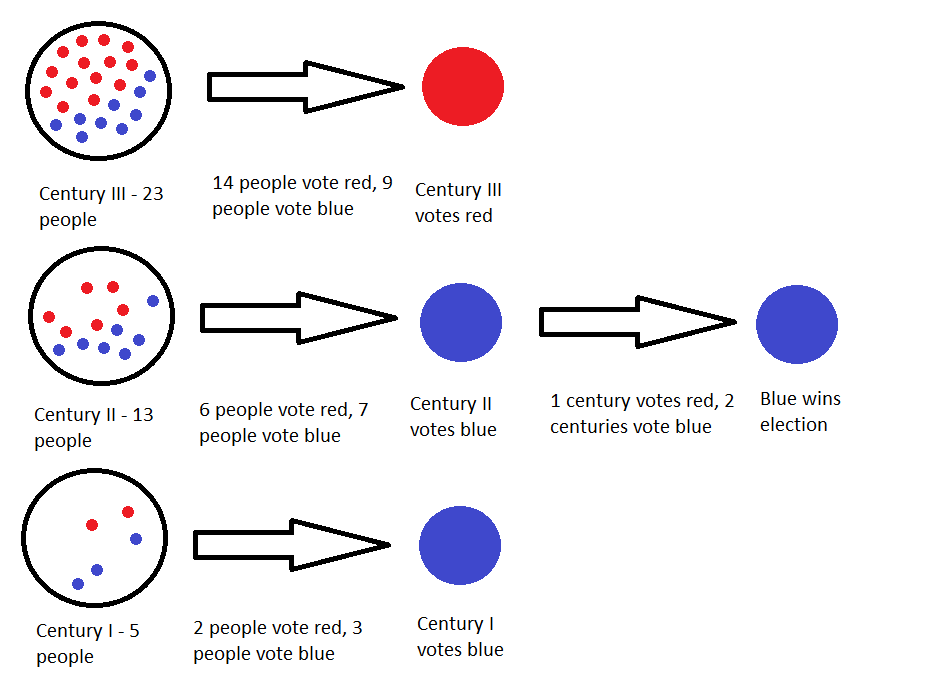

Everyone who could vote in Rome was registered into a group called a century. Which century a person was put into was determined by how rich they were, and whether or not they were over 45. For example, the richest people over 45 would be in a century together, as would the poorest people 45 and under. Centuries were grouped into classes I to V, with class I being the richest and class V being the poorest. There was a class above class I called the “equites”, reserved for the very wealthiest people. There was also a class below class V called “capite censi”. Capite censi translates as “counted per head”, and represented the people who had no money or property that was worth counting, so only the person themselves (their “head”) could be counted. Each of the 7 classes were split into seniores (over 45) and juniors (45 and under).

Each century had one vote – a century’s vote would be given to whoever the majority of people in the century voted for. The candidate that the most centuries voted for would win. This was the same when voting about whether to pass a bill – if most centuries voted for the bill, the bill would pass and vice versa.

However, it is important to understand that not every century had the same number of people in it. The wealthiest centuries often only had a few hundred people in them, whereas the poorest had many thousands. Since each century only had one vote, this meant that the poorest people had less than one thousandth of a vote, whereas richer people could have one hundredth of a vote. Therefore, this system could be classed as unfair because rich people had a larger say in the running of Rome.

Voting would begin when all members of the assembly met on the Campus Martius. There was an enclosure for each century, and members of the century would meet in their enclosure to vote. Voting would then take place through secret ballot, meaning other people couldn’t see who or what someone had voted for. This helped to prevent corruption, since it is hard to bribe or blackmail someone if you don’t know whether they actually voted for what you wanted them to. The equites class and class I voted first, followed by class II, then class III etc.

The comitia centuriata was arguably the most important of all of the Roman assemblies. They elected the most important officials (consuls, praetors and censors), could make laws and decided whether or not to go to war. They could also be called by praetors or consuls to listen to and discuss certain matters.

The main job of the comitia tributa was to elect officials such as Aediles and quaestors. Everyone in the comitia centuriata was also in the comitia tributa. However, while people were split up into centuries based on wealth and age in the comitia centuriata, in the comitia tributa they were split up into tribes. Everyone in Rome belonged to one of 35 tribes, based on where they lived.

However, this system was still biased towards the rich. This was because most poor and middle class people lived in Rome, but Rome was split into only 4 tribes. The other 31 tribes were mainly rural. The land in these 31 tribes was largely owned by senators, the incredibly rich patricians who owned massive amounts of land and made their money by renting it out to others. Therefore, senators were often one of only a few people registered in their tribe, whereas poor plebeians would have shared their tribe with thousands of people. Since each tribe only had one vote, similar to the centuries in the comitia centuriata, this meant that rich landowners had much more power than poor plebeians.

Was the Comitia Centuriata fair?

Explain how the voting system in the Comitia Centuriata worked.

Was the Comitia Tributa fair?

Explain how the voting system in the Comitia Tributa worked.

The main advantage of the voting system was that most male citizens were able to vote, even those who had no money or property. Even though the system was unfair, the poor still had a say in what happened in Rome, which was relatively unique for its time.

Of course, on the other hand, there were many people who couldn’t vote. This included women, slaves and everyone who was born in one of Rome’s colonies. Most of the people living in Italy and the rest of the Empire couldn’t vote, because they weren’t born in Rome.

Another strength of the voting system was that they used secret ballot to vote. This reduced the possibility of corruption, since it was harder to threaten someone to vote a certain way if you had no way to tell who they would end up voting for.

There is no doubt that the Roman voting system gave more political power to the rich rather than the poor. However, it could be argued that by favouring the rich, the system favoured those who had more at stake in the Empire. Therefore, those with the most to lose had the most say. On the other hand, the fact that the rich had the biggest say meant that they would only vote for things that would benefit themselves and other rich people. This meant there was much less chance for poor people to be able to improve their situations, because they didn’t have much of a say in the political system: the poor would stay poor, and the rich would stay rich.

No one could vote by proxy, everyone had to go to Rome to vote in person. For people who lived far away from the city of Rome, it often took so much time and money to get there that it was impossible to vote. Although these people had the vote in theory, in reality it was practically impossible for them to have their say in the political system.

There was no minimum number (quorum) of people needed to show up to vote in order for the vote to take place. For example, if only 10 people showed up in a century of 10,000, these 10 people would each hold 1/10th of a vote. Therefore, In reality a vote could be decided by only a small number of people, which isn’t very democratic. This meant that there was no motive for politicians or people interested in politics to try to get a high percentage of people to vote, because if they didn’t vote then the people interested in politics would get a larger share of the vote. Because no one was motivated to encourage people to vote, this could likely lead to a small turnout for voting.

Although secret ballot voting should have made bribery less common, in reality voters were frequently bribed – less wealthy political candidates even took out loans to pay for these bribes. This meant it was extremely hard to be successful in politics unless you had money – poor people would never be able to be elected as officials. Furthermore, bribery meant that it wasn’t the best person getting chosen for the job, it was the most corrupt person. Similarly, an unfair or bad bill could pass just because a few wealthy people wanted it to.

Keep in mind that the above video refers to the Assemblies using their English names. Assembly of the Centuries = Comitia Centuriata, Assembly of the Tribes = Comitia Tributa and Assembly of the Plebs = Concilium Plebis

Do you agree with the argument that rich people should have a greater say in politics than poor people?

Overall, do you think that the Roman voting system was fair?

Were there more advantages or disadvantages to the Roman voting system?

In the Roman Republic, many important public buildings and other structures had to be built and maintained. Examples of these include roads, aqueducts, bath houses and amphitheatres. However, the government didn’t build these themselves. Instead, they paid private individuals to do the work for them. These private individuals were normally equestrians, and by being paid to do work for the government they entered into a public contract. As these contracts were usually very lucrative, there was often a lot of competition between equestrians to obtain them.

Before learning about the different types of officials in Ancient Rome, it is important to understand the difference between imperium and potestas. Imperium meant the power to control the army, pass laws and enact punishment. An official with imperium could sentence someone to death and execute them. Therefore, imperium was a massive and very important power. Only three types of officials – consuls, dictators and praetors – had imperium. These were the three most powerful types of official. Lictors were the bodyguards of any offcial with imperium. They carried a bundle of rods called fasces. The number of lictors can be seen to symbolise the amount of power an official had – dictators had 24 lictors, consuls had 12, and praetors only had 6.

Potestas, on the other hand, was the power of an official to enforce the law in order to complete their job. However, this power was very limited: they couldn’t make the law and could only enforce the law within their area of work. For example, if an aedile wanted to enforce the law they would only be able to do so if it helped them carry out their job. This ensured that officials wouldn’t use this power for their personal gain. All officials had potestas.

What were the main differences between imperium and potestas?

Consuls were some of the most powerful officials in Ancient Roman politics. Every July, two consuls were elected to serve for a year – sometimes they could have their time extended for longer than a year, and in this case they were referred to as proconsuls. Consuls were elected by the Comitia Centuriata. Because consuls were so powerful, a person usually had to wait 10 years after acting as a consul to be elected as a consul again. This ensured that no one person would be able to rule as consul year after year.

A consul had imperium. This meant that they could command the army, arrest and punish citizens at will, and take auspices to determine what course of action should be taken. Taking auspices was a religious practice that involved using the flight of birds to determine what the gods were thinking, and whether they approved or disapproved of a specific course of action. A consul could call for the comitia – the Roman assembly – to meet, and could preside over the meeting. Finally, consuls also had the right of veto. This meant that they could veto (reject) the decisions of other consuls – if one consul wanted to do something but the other didn’t, then it wouldn’t happen. This helped to curb the otherwise immense power of consuls. By the 1st Century, one of the consuls had to be plebeian. This allowed non-aristocratic, non-patrician interests to be better represented.

Do you think that Consul was a particularly dangerous position? This means, do you think consuls would have been easily able to use their power to overthrow or impede democracy?

How likely do you think it was for consuls to be corrupt? Why?

Were consuls a benefit or a weakness to the Roman Republic?

Like consuls, praetors were also elected by the comitia centuriata. Praetors were in office for a year. In 80 BCE there were only 8 praetors, but this increased to 16 by 44 BCE.

Similarly to consuls, praetors had the power of imperium. This meant that, like consuls, they could command the army and punish citizens. They were very important legal authorities in Rome because of their ability, through use of imperium, to interpret the law and carry out sentencing of criminals. In particular, two praetors every year had significant legal positions. One was called the Praetor Urbanus, and dealt with all criminal cases and legal disputes in Rome. The other was called the Praetor Peregrinus, and dealt with legal matters relating to foreigners. In many ways, these were the Roman equivalents of judges. The rest of the praetors served as governors for many of the colonies of the Roman Empire. At the start of their term, praetors had to make a speech announcing their intentions and the principles they would follow while in office. However, while some stuck to their public goals, others became corrupt and used the power for their own gain. Furthermore, praetors weren’t all-powerful – they had to listen to other praetors and the consuls, as well as the senate.

Do you think that Praetor was a particularly dangerous position? This means, do you think praetors would have been easily able to use their power to overthrow or impede democracy?

How likely do you think it was for praetors to be corrupt? Why?

Were praetors a benefit or a weakness to the Roman Republic?

There were four aediles elected every year – two from a patrician family, and two from a plebeian family. Therefore, plebeian interests were fairly well-represented by aediles. Aediles were elected yearly by the comitia tributa.

Aediles served two main roles. The first involved policing the streets and market places of Rome – they controlled traffic, caught and disciplined minor offenders such as petty thieves, and ensured the smooth running of the republic by supervising sewers and the water supply. They also secured the government’s supply of grain. This was used to provide the corn dole for poor Romans, so doing this job badly could drastically affect the public’s opinion of a person because if there was no corn dole many would starve.

Why was the election of aediles fairer than that of many other positions?

How likely do you think it was for aediles to be corrupt? Why?

Were aediles a benefit or a weakness to the Roman Republic?

How could the way someone performed their job as an aedile influence the public’s opinion of them? You should mention at least 2 ways.

20 Quaestors were elected by the Comitia Tributa every year. While quaestors didn’t have imperium, they did have some power because they had a lot of control over the treasury and state archives. Therefore, they could control the government’s funds. This meant they could form powerful alliances with factions of the military and other prominent officials by increasing or reducing the amount of money these groups were given. Therefore, quaestors were often quite open to corruption.

Quaestors were in charge of keeping track of how much the army was paid. If they didn’t do their job correctly, therefore, this could lead to a revolt of angry, unpaid soldiers.

Apart from control over finances, quaestors often aided consuls as secretaries, or praetors as financial officials. Anyone who was elected as a quaestor also automatically became a lifelong member of the senate.

What could have been the impact of a quaestor doing their job poorly on the republic?

How likely do you think it was for quaestors to be corrupt? Why?

Were quaestors a benefit or a weakness to the Roman Republic?

2 censors were elected by the comitia centuriata every 5 years. However, they only served for 18 months, meaning that there were no censors for three and a half of those five years.

Every 10 years, a census is completed by British adults. This census is a form that includes personal details such as age, gender, religious beliefs, race, etc. It is a way for the government to keep track of everyone living in Britain, and allows useful statistics to be created for academic use. Censuses were also used in Ancient Rome, although back then it was much more basic, and was essentially just a list of names. It was important for the state to know how many people were in Rome and where they lived, and this job was done by the censors.

However, a censor’s job was not only limited to this. Censors had many other very important duties. For example, they controlled who public contracts were given to. They also controlled who public lands were leased to. Similarly to quaestors, this meant censors were open to corruption and could form strong alliances with other influential people by deciding to give contracts to certain people.

Censors were in charge of public morals, and could expel senators from the senate if they thought they lacked morality. Given how influential the senate was, censors had a massive amount of power because they could in many ways control who was in the senate. The fact that they were in charge of “public morals” meant that their own personal morals could influence those of the entire republic – this was an incredibly powerful position to be in.

Do you think that Censor was a particularly dangerous position? This means, do you think censors would have been easily able to use their power to overthrow or impede democracy?

How likely do you think it was for censors to be corrupt? Why?

Were censors a benefit or a weakness to the Roman Republic?

Although in modern times the word “dictator” has come to mean someone ruling a country with absolute power for life, in the Roman Republic a dictator was just another official. Dictators, unlike most other officials, weren’t elected. Instead, they were appointed by consuls in a time of emergency. In order to deal with this emergency, the dictator was given full control over all of the other magistrates. This was so that emergency situations could be dealt with quickly and decisively by one man, rather than by many people squabbling and arguing over what should happen, and blocking one another’s ideas through use of veto. However, the fact that dictators had near-total control over Rome made corruption very possible.

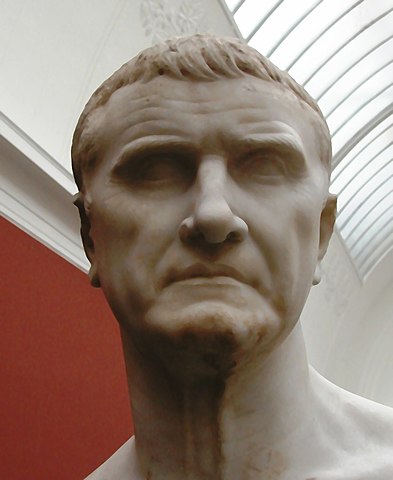

Above is Julius Caesar, who was initially appointed dictator by the Senate and then later appointed himself “dictator for life”, officially ending Roman democracy.

Dictators could only hold power for 6 months. Some dictators left their positions before the 6 month mark had passed, if the crisis ended early. However, Julius Caesar managed to essentially become Emperor of Rome in all but name by making himself “dictator for life” – he originally became dictator by being appointed to the position, but then extended his power past 6 months. Therefore, some people managed to take advantage of the position of dictator to give themselves more power and abuse the system. Given that Caesar’s rise to power marked the end of Roman democracy, dictatorship can be seen as the most dangerous role, since it eventually led to the destruction of the Roman Republic and democracy in Rome.

Do you think that dictator was a particularly dangerous position? This means, do you think dictators would have been easily able to use their power to overthrow or impede democracy?

How likely do you think it was for Dictators to be corrupt? Why?

Were Dictators a benefit or a weakness to the Roman Republic?

Every year, 10 tribunes were elected by the Concilium Plebis, and they served for one year. Although they didn’t have imperium, so didn’t have the same amount of power as officials like consuls, they did play a very important role in government because they had the power of veto over all officials, including consuls. This meant that even if all other officials wanted something to happen, but one Tribune of the People didn’t, then it wouldn’t go ahead. This allowed Tribunes to represent the views and needs of the common people, which most other officials, being patricians, wouldn’t have insight into. Of course, the power of veto could be a gateway to corruption, because Tribunes could use their power to prevent a course of action from being taken to harm their enemies and form alliances.

Tribunes also managed to represent the views of the public because they were able to attend Senate meetings. Given how powerful the Senate was in Rome, this was a very important power. However, instead of using this power to challenge senators on behalf of the people, many tribunes just became puppets for the senate. Tribunes were allowed to call meetings of the assembly and propose laws to be passed, but they often only proposed laws that the Senate wanted. They could therefore help to expand the power of the already very powerful Senate.

Tribunes were “sacrosanct”. This meant that if they were attacked, there would be much more serious consequences than if an ordinary person had been attacked. This was to ensure that, as representatives of the common people, they weren’t threatened into silence by powerful people who didn’t want their own interests disrupted. However, this also may have led to abuse of power because Tribunes felt they could do whatever they liked without consequences.

How likely do you think it was for Tribunes to be corrupt? Why?

Were Tribunes a benefit or a weakness to the Roman Republic?

Rank the officials from most to least powerful, in your opinion.

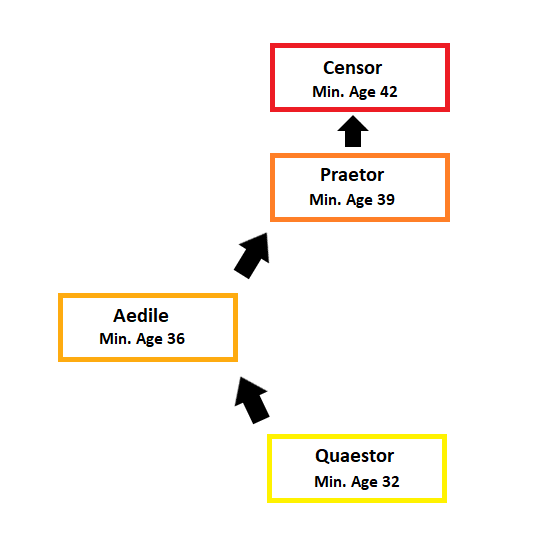

A young poltitician couldn’t just immediately be elected as a consul. Instead, there were a number of steps that a person had to go through. The first step, before a man could hold any political office, was 10 years of military service.

After this, the first rung on the ladder was the position of quaestor. The minimum age for a Quaestor for 30. Next was aedile (minimum age 36), praetor (minimum age 39) and finally consul (minimum age 42). There had to be a 2 year gap between someone taking up any two of these positions. By making sure that everyone had to be the least powerful official before they could be the most powerful official, this ensured that those with the most power had at least a few years experience of holding political office, so they had more experience. Furthermore, all officials had to have military experience, which was very important for Roman officials because Rome was often at war.

Note that Tribunes of the People, Censors and Dictators weren't part of the Cursus Honorum.

In your opinion, what are the advantages of the cursus honorum? What about the disadvantages?

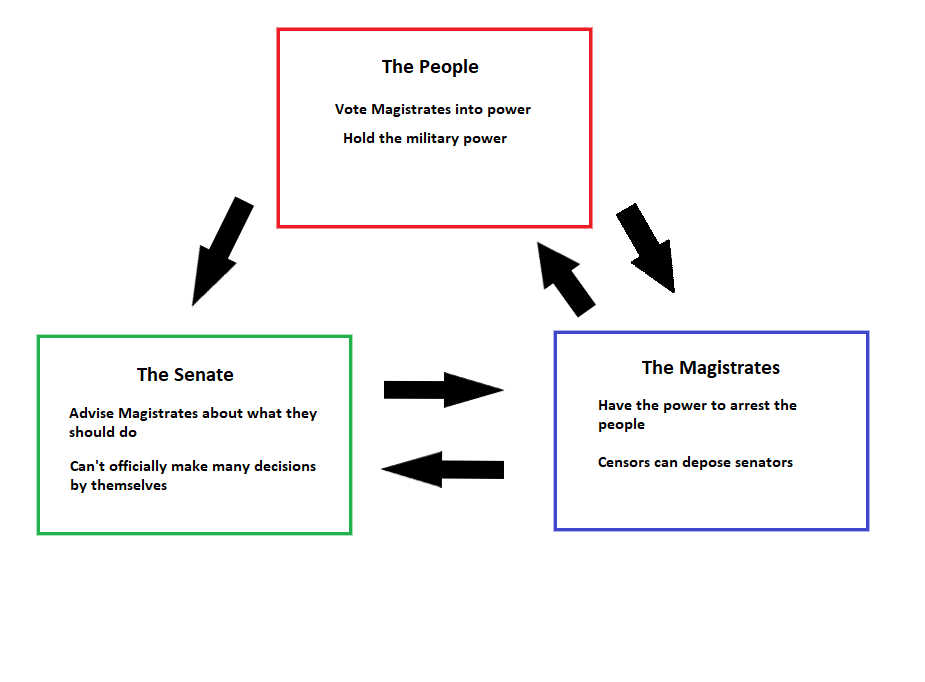

In Rome there was, at least in theory, a balance of power between the magistrates (officials like consuls, praetors, quaestors and aediles), the Senate and the people. This meant that each group could keep the other groups in check, and no group would be able to have complete power over the Roman state. For example, the people could elect the magistrates, so magistrates had to promise to do what the people wanted them to. The people also had a large amount of power because they were in the army: they were trained fighters and this meant that the nobles (including senators and magistrates) couldn’t survive without the common people. One of the magistrates, the censor, could remove senators from office for not being moral enough. Furthermore, there were many things senators couldn’t do on their own without a magistrate’s approval. Certain officials, such as consuls and praetors, could arrest and punish members of the public. Finally, senators had a certain amount of power over officials because they had more knowledge and experience so in many cases officials had to listen to them.

However, while there was supposed to be an equal balance of power between these three groups, in reality the senate had the most power. Since most officials served in office for only a year, they couldn’t implement long-term policies – other officials would just change them later on. Furthermore, they were often inexperienced and couldn’t build up a good knowledge of the social and political climate since they were in office for such a short period. Therefore, they were usually very reliant on the Senate, who had the rest of their lives to build up knowledge and experience that would help them make good decisions. Since the Senate became so powerful, this made other officials even less likely to go against them, since making such a powerful enemy was quite dangerous. Also, the Senate weren’t elected by the people, so they weren’t held accountable if their actions went against the wishes of the public. All of these facts contributed to the enormous amount of power held by the Senate.

Do you believe that there was balance of power between the people, the magistrates and the senate?

The strengths and weaknesses of the Roman voting system have already been discussed, but you must also be aware of other issues with the rest of the Roman Republic.

The fact that officials were usually only in office for about a year prevented any one person from having a lot of power – it spread the power out among a number of people. This helped to prevent corruption and ensured no one person would gain enough power to turn the democracy into a dictatorship. On the other hand, it meant these officials couldn’t build up experience and knowledge of the political climate or the current state affairs, so they remained relatively inexperienced and therefore less able to make the right decisions and do their job well. It also meant that they were more easily manipulated and controlled by the Senate, who did have time to build up this experience.

The attempt to balance powers between the officials, the senate and the people ensured that everyone was accountable to someone, and no one could do whatever they liked without consequences. This prevented corruption and kept democracy safe. However, this was only the case if the balancing of powers actually worked. In reality, the Senate had most of the power.

People served in the Senate for life. On the one hand, this allowed them to build up a lot of experience, meaning they could make the best decisions for the republic. However, this gave a lot of power to the members of the Senate, because they never lost their authority. Magistrates usually listened to the Senate's advice, which could easily lead to corruption, because members of the Senate could make other officials do things that would benefit them.

There were about 300 senators in the senate. The large number of senators ensured that no one person held absolute power – the power was diluted throughout many people. Therefore, no single person could have the power to topple democracy. The large number also allowed for better debate, since any decision had to have the agreement of many people and therefore concessions had to be made. Since better decisions are usually made when many people have input, this can be seen as a strength.

An issue with senators was that they weren’t elected by the people. This clearly wasn’t democratic. However, by 80 BCE all quaestors automatically became senators, and quaestors were elected. So, in a way senators were democratically elected.

The cursus honorum ensured that the most powerful officials had to have some political and military experience before they could get into office. This ensured that they had the knowledge to successfully carry out their job. However, the age restrictions on being elected as an official meant that a lot of young talent was likely wasted – a person with less talent who was over the age limit would get the job instead of a person with more talent who was under the age limit.

Most officials had to be patricians. Even if they didn’t have to be, a good family name counted for much more than talent in Roman elections. Therefore, this meant that many incompetent people with well-known family names were in office, and many people with the talent and ability but not the right family had their ability wasted – they could have contributed to the success of Rome but weren’t able to.

After someone had been a consul, they had to wait for 10 years before they could be elected as a consul again. Furthermore, after someone had been any kind of official, they had to wait 2 years until they could be elected into another position. This helped to ensure that one person wouldn’t be in power constantly.

However, these rules would mean nothing if they weren’t properly enforced. And, as it turns out, in Ancient Rome they weren’t: there were many examples of successively elected consuls. For example, Gaius Marius was consul 7 times in only 21 years: he was consul for 5 of those years consecutively. Therefore, the rules that were put in place to protect the republic and ensure no one got too much power were effectively useless.

By the 1st Century, 1 of the 2 consuls and 2 of the 4 aediles had to be plebeian. Furthermore, the Tribunes of the People were also all plebeians. This allowed the plebeians to have a greater say in the running of Rome. On the other hand, it was almost always rich plebeians who got into these positions of power – the poor were as unrepresented as ever.

The Tribunes of the People were sacrosanct, meaning it was a very severe crime to attack them. This allowed them to work for the benefit of plebeians without having to fear intimidation or harm from the rich patricians they were going against. However, being sacrosanct also made many tribunes feel secure enough to engage in corruption and other activities that would benefit them – they felt they could do whatever they wanted without being accountable.

There was more than one of every official. For example, there were 2 consuls. Furthermore, consuls, praetors and tribunes all had the power of veto. This ensured that no single person had all of the power, so that democracy was safe. It also helped to reduce corruption, since if one official was doing something that would benefit them rather than the state then another official could veto them. However, the power of veto meant that officials could squabble amongst themselves, and if they disagreed then nothing could be done. For example, if all officials wanted a different solution to a problem, then they would all veto each other’s solutions and nothing would be done.

One solution to this issue was the position of dictator. Dictators had absolute power for a short while in the case of an emergency. This allowed for the quick and decisive response that was often needed in emergency situations. However, the absolute power that dictators had could be abused. For example, Caesar managed to extend his role to be “dictator for life”, ending democracy. So, the position of dictator was very dangerous for the Roman Republic.

Another very powerful position was that of the censor. Censors could remove senators for being immoral, and therefore had a lot of influence over the senate, the most powerful political body in Rome. This could lead to corruption, because they could use this power for their own gain. However, this did help to keep the senators somewhat under control, as it was one of the only checks on their power.

Overall, were there more advantages or disadvantages of the Roman Republic? Was it a good system?