The Delian League was Athens’s Empire, established in 478 BCE. It grew to encompass over 300 different poleis, and helped to cement Athens’s position as one of the major powers of the Ancient Greek world. However, the Delian League did not begin as an Empire. In fact, it was a coalition of equals, with each poleis having a say in what the League did. These poleis voluntarily chose Athens as the leader of the Delian League, primarily because of its powerful navy. However, Athens made a series of choices that increased their authority until they had successfully created an Empire, subduing anyone who dared to rebel against their new-found power.

In this section, the members of the Delian League other than Athens will be collectively known as the allies.

The revolt was unsuccessful, with Persia emerging victorious. However, perhaps realising the potential threat a second more coordinated revolt could pose, the Persians made a number of concessions. The tributes (money paid to Persia by its colonies) from Ionian poleis were reevaluated to reflect the size of the city, leading to less of a financial burden for the Ionians. Furthermore, tyrannies were replaced with democracies in Ionia.

One significant impact of the Ionian revolt was that it singled out the Athenians as enemies of the Persians, since they had supported their fellow Greeks. Persia was determined to punish Athens for this perceived threat to its authority. This was attempted during the expedition of 490 BCE, when Persian forces invaded further into Greece in an attempt to subjugate Athens. Persian forces met a coalition of Athenians and Plataeans (from the Greek polis of Plataea) at Marathon, a plain within the Athenian territory of Attica.

It seemed obvious who would win. The Athenian side had only about 10,000 soldiers in total (roughly 9,000 Athenians and 1,000 Plataeans), while the Persians had about 12,000 (another 12,000 had split off to attack Athens directly). The Persians were sure of their victory.

However, the Athenian side had a clever general, Miltiades, who came up with an ingenious strategy. The Athenian forces were arranged in a line as normal, but while the middle of the army had comparatively few soldiers, the sides had many soldiers and were therefore the strongest areas. When the Athenians faced their enemy, therefore, the Persians pushed against the weak middle while the strong sides wrapped around them. The Persians became surrounded by Athenian soldiers, and were killed in massive numbers with few Athenian casualties. One count (by historian Herodotus) says that 6,400 Persians and only 192 Athenians were killed, although the numbers vary wildly depending on the source.

According to legend, an Athenian messenger ran the almost 25 miles back to Athens to announce the victory. After relaying his message, the messenger apparently collapsed and died from exhaustion. This was the first marathon ever run – successive marathons remained close to 25 miles in length until 1908, when it was increased to 26.2 miles.

The Spartans had intended to lend the Athenians aid during the battle of Marathon, but by the time they had arrived the fighting was over – Athens had repelled the invaders without them. Before this, Sparta was regarded as the uncontended powerhouse of the Ancient Greek world, with a bigger and better trained army than the other poleis. However, the fact that Athens emerged victorious despite horrible odds and without Spartan help marked the start of their rise to power. The battle also increased the sense of pride Athenian citizens felt for their city.

In 482 BCE, a discovery that would prove to be essential to the success of Athens was made: silver was found in the Laurium mine in Athens. So much silver, in fact, that Athens found itself very wealthy almost overnight. Though there was much debate over what to do with this new-found wealth, the citizen Themistocles eventually persuaded the Assembly to spend it on a new fleet of Triremes. This turned out to be a key decision that affected much of the rest of Athenian history.

The Persians decided to try again to defeat Athens in the year 480 BCE. The Athenians were worried they would lose against such a massive Empire. Therefore, they decided to consult the Delphic Oracle to determine the likelihood of victory. The resulting prophecy wasn’t exactly encouraging, given it predicted the downfall of Athens. The citizens’ one hope, however, was to have faith in their “wooden walls”. Many Athenians assumed this meant they were to hide behind the thorn bushes that surrounded the Acropolis, a fortified hill in Athens – this would be their wooden wall. Themistocles again managed to convince his fellow citizens otherwise, however, arguing that these “wooden walls” were in fact the newly built Athenian navy. His arguments won out, Athens was evacuated and the navy prepared for war.

Meanwhile, the Spartans were fighting their own battle with the Persians. They led a coalition of 6-7,000 Greek warriors to defend Thermopylae in 480 BCE. The outcome was a mixed bag for the Greeks. Their navy had a lot of success, particularly since the weather helped them and hindered the Persians, but their land campaign was disastrous. Successive failures caused most of the Greek army to retreat, leaving only 1,400 soldiers, including the Spartan leader of the coalition and roughly 300 Spartan soldiers. Then, a local Greek man showed the Persians a route through the mountains that allowed them to cut off any option of retreat for the remaining Greek army. The Spartan commander discovered this just in time for escape, and all troops except the Spartans and the Thebans retreated. In the end, the Thebans surrendered, but the Spartans fought to the death.

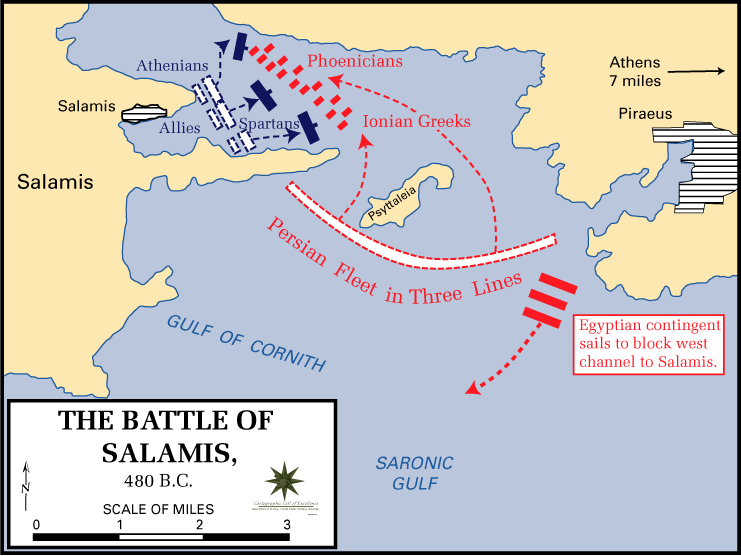

About a month later, the Athenians faced the battle they had been preparing for. After Thermistocles had won the “wooden walls” debate, it was decided that the city of Athens would be evacuated: its people fled to the neighbouring poleis of Aegina, Troezen and Salamis. Greek ships (the majority of which were Athenian, aided by help from poleis like Sparta and Corinth) were positioned in the Bay of Salamis, a narrow strait of water where the battle would take place. The Persians arrived in Athens, then looted and burnt the city to the ground. In order to lure them to the battleground, Themistocles wrote a message to the Persians stating that he wanted to betray Athens and become a Persian ally. He advised that they come to the Bay of Salamis to block off Greek retreat, and promised that once they had done so he would turn his ships against the other Greeks. The Persians believed him, and fell into Themistocles’s trap. The Persian ships found it hard to manoeuvre in the narrow waters, and because there was so little space the ships could only advance a few at a time, reducing the advantage brought by their vastly superior numbers (the Greeks had about 380 ships, the Persians 600-1200). With these tactical advantages, the Greeks won victory: 40 Greek ships were sunk, compared to 300-400 Persian ships.

This battle saw the emergence of Athens as a major naval power – their tactics and fighting skills in the waters of Salamis proved their expertise. This navy would prove essential when Athens began to build its Empire.

The Battle of Salamis wasn’t the end of the fighting between Persians and Greeks, but it did mark the turning of the tides that eventually saw the Greeks emerge as victors over their much larger foes. The Greek victories during the Battle of Plataea, the Battle of Mycale, and the successful sieges of Thebes (a Greek polis that had sided with the Persians) and the Persian town Sestos consolidated the Greek advantage – the Greeks were now on the offensive. The war with the Persians saw a greater unity among the Greeks – although each Greek polis had very a different culture and government, they worked together to fight a bigger enemy, as shown by the fact that most of the battles were fought by a coalition of different Greek poleis. This idea of Greek unity directly leads into the formation of the Delian League.

Give as many reasons you can think of as to why there was a need for an alliance between a number of Greek poleis?

What do you think that Persian concessions towards Ionia did for the morale of the citizens of Greek poleis?

Would Greeks be more likely to think they had a chance of defeating Persia before or after these concessions?

What was the importance of the Laurium silver mines with regards to Athens’s power and its eventual place as leader of the Delian League?

What approach did the Persians take to battling the Greeks (e.g. brute force, good tactics, strategic use of the land)? What approach did the Greeks take? What might have been the reason behind their respective approaches? (You may wish to consider the sizes of Persia and a Greek polis like Athens.)

From the point of view of other poleis, why might Athens be a good choice to lead the Delian League?

The Persians retreated from Greece in 479-8 BCE, but the threat of another invasion still remained. Many Greek cities (including Athens during the Battle of Salamis) had their cities destroyed and pillaged, and needed money to make up for their losses. Finally, Persia still occupied a lot of Ionian cities, which shared the same language and worshipped the same gods as poleis like Athens. Many Greeks, particularly Athens which as a newly democratic nation was keen on self-determination, thought these cities should be free from Greek influence.

Because of their cooperation while battling the Persians, Greeks realised that the best way to achieve these aims was to work together. Therefore, the Delian League was formed in 478. It had three main aims: to compensate for the looting and destruction of their cities by doing the same to the Persians, to liberate all of Ionia from the Persians, and to protect Greece from any subsequent attack by the Persians.

A leader had to be chosen for this new organisation, and the League had two main options: Sparta, the old military power, experienced with fighting on land, or Athens, the new naval power. Originally, it had been assumed that Sparta would lead, but Sparta itself was rather unwilling to do so. At the time, it was facing great internal strife, partially caused by large slave rebellions, and so it didn’t have the time or strength to devote to issues outside Sparta when it was trying to maintain order within the city. So, attention turned to the Athenians, who were only too eager to take charge.

Summarise the main purposes of the Delian League.

Why might it make more sense for Athens (powerful in the water) to lead the Delian League than Sparta (powerful on land)? You may wish to look at a map of the Greek poleis in the Delian League.

Although the leader of the Delian League was Athens, each of the poleis within the League could vote on what actions the League would take. Athens also had a vote, though theirs carried the same weight as all of the other votes added together. Even so, at this point the Delian League was essentially a partnership between each of the poleis within it. No member was subservient towards another; no member was a colony of another.

The Delian League was named after the island of Delos, which represented the idea of equality that the League was founded on. After all, Delos was a neutral ground in Ancient Greece: it wasn’t owned by any of the poleis in the League, nor by anyone else. As well as being the namesake of the League, it was also the League's official meeting place and was the location of its treasury. Therefore, it was the League’s centre of power.

Participation in the Delian League was, in the beginning, voluntary. However, when a member joined, they completed a ceremony during which they would drop an iron ingot in the ocean, stating that they would be a member of the League until the iron floated to the surface. Since iron doesn’t float, they were essentially promising that they would be loyal to the Delian League forever. Athens would use this to their advantage later, in order to force poleis not to leave the League.To be successful the Delian League needed both money and ships. Some poleis contributed ships to the League, and those who were didn’t want to do so gave money instead. This money was held in the Treasury at Delos for the League’s use. As the Delian League aged, many poleis became unwilling to sacrifice the lives of their men by providing ships, and preferred to contribute money instead. However, this meant that almost all of the League’s navy was contributed solely by Athens. While the armies of other poleis gradually became small and untrained (because of the protection afforded to them by Athens), the Athenian navy got stronger, accumulating more battle experience as time progressed. The military power within the League was clearly unbalanced, and this would allow Athens to take full control of the other poleis by force.

How could the fact that members of the League promised to stay in the Delian League forever be used by Athens to justify their actions later on?

Why was Athens able to turn the Delian League into its empire?

Although the Delian League began as a partnership of equals, over time Athens managed to transform it into an empire. This transformation didn’t occur overnight – it was a creeping process that happened at different times for different poleis.

One of the first signs of the formation of an empire was when the Athenians forced the Greek polis of Carystus to join the Delian League in 472 BCE. They justified this because they thought Carystus would ally with the Persians and they were determined to prevent this, but the actions of the Athenians at this point directly went against the principle of self-determination on which the Delian League was based.

A few years later, in 469, the polis Naxos wanted to leave the Delian League. Athens had other ideas – they besieged Naxos until it surrendered. After this, Naxos lost its sovereignty, becoming a colony of Athens. It lost its military, and paid tributes directly to Athens.

By 468, the threat of Persia had largely been solved. Given that this was the main reason many poleis had joined the Delian League, many now wanted to leave. By this point, however, almost all of the poleis had opted to give money rather than ships to the League, so Athens alone had a powerful navy and therefore had all of the military power. Athens didn’t want the Delian League to disband, and argued that the oath members had made when they joined (that the alliance would stand as long as the iron ingot did not float) meant they couldn’t leave the Delian League. They prepared to keep members in the League by force if need be.

This was put into action in 465, when the polis Thasos wanted to leave the Delian League. Like with Naxos, the Athenians besieged Thasos. The siege lasted 2 years but was eventually successful, and Thasians were severely punished. Their navy was confiscated, their city walls destroyed and their mint closed. They were forced to pay a large fine to Athens. Like Naxos, they paid a yearly tribute to Athens. Finally, much Thassian-owned land was confiscated and given to Athenians.

Aegina was a polis that was geographically close to Athens but wasn’t in the Delian League. In 456 BCE, bad relations between the two nations led to a siege of Aegina by Athens. However, rather than their personal navy Athens used Delian League forces, which were not supposed to be used in individual conflicts between specific members of the League. Athens was using the resources of the League for its own personal use, making the Delian League appear more and more like Athens' Empire.

After a two year siege, Athens captured Aegina. It then forced Aegina to join the Delian League, confiscated its navy and forced it to pay an annual tribute to Athens. So, Athens’s empire continued to expand.

After a major defeat in 456 BCE, Athens unilaterally decided to move the League treasury from the neutral island of Delos to Athens itself. Athens therefore took full control over the League’s finances. On top of this, the donations made to the League were now mandatory, and were called tributes to Athens. Poleis could no longer choose whether to give ships or money – this was decided by Athens.

Finally, in 449 BCE peace between Greece and Persia was achieved. The treaty they agreed to was called the Peace of Callias. Athens, for their part, agreed that they wouldn’t attack Persia and gave up the claims they had to Cyprus and Egypt. Persia agreed that the Greeks of Asia Minor would be free from Persian control (this included the Ionian Greeks), Persia would stay at least 3 days’ march away from the coast of Asia Minor and wouldn’t send ships into the Aegean sea (the sea that bordered most Delian League members, including Athens). Therefore, by this point all of the aims of the Delian League had been accomplished. In a normal situation, this would cause the League to disband, but Athens showed no sign of letting that happen.

In your opinion, were poleis like Naxos and Thasos treated fairly by Athens?

Why was it unfair for Athens to use League forces to fight its personal battles?

Why was moving the League treasury from Delos – which was a neutral island – to Athenian territory important?

Why should the Delian League have been disbanded in 449 BCE?

Once the League’s Treasury came to Athens, Athenian citizens essentially had full control over how the finances were spent. The tributes paid by the allies were used not to benefit the League as a whole but to finance Athens’s domestic matters. For example, the money was used to pay jurors and political officials like archons, build temples and maintain the Athenian navy. League money was also used to build the Parthenon, arguably the best-known piece of architecture in Athens.

Because Athens had the best military in the League, this meant they could force the allies to pay tributes (either in the form of money or ships) to Athens. They could change the amount the allies paid, and the price tended to increase for each polis as time progressed. Certain nations were also given unfairly large tributes to pay, because of Athens’s personal feelings towards that nation. For example, Athens historically had a bad relationship with its neighbour Aegina. Athens besieged Aegina but the polis put up a fight, only giving in after 2 years. After Aegina was forced to join the Delian League, it had to pay the single largest yearly tribute to Athens despite not being the largest polis in the League.

Those allies who were ordered to contribute ships rather than money in their tributes to Athens often lost men during the personal conflicts Athens had with other poleis. For example, Athens had a bad relationship with Sparta throughout its empire period, and fought them directly during the Battle of Tanagra in 457 BCE. During this battle, League forces, not all of which were necessarily Athenian, were forced to fight and sacrifice their lives for an issue that only affected Athens. The siege of Aegina is another example of using League forces for Athens’ personal gain.

Garrisons (groups of troops) were placed at a number of ally poleis in order to ensure they obeyed Athens and didn’t rebel. Many allies, particularly those who had tried to rebel, were forced to make a pledge of allegiance to Athens, saying that they would pay their tributes, wouldn’t rebel and would be obedient to the Athenian people. For the Greeks, who thought being treated as inferior to others was a massive disgrace, this would have been incredibly humiliating.

Tyrannies and oligarchies (rule by the elite few) were replaced by democracies throughout the Delian League. This allowed the common citizens in these poleis much more power than they had ever had before. On the other hand, many people may not have wanted a democratic government. This may have made the introduction of democracy, ironically, undemocratic.

Athenian coinage was introduced across the Delian League. Poleis’s own mints were closed, and their native coins were melted down. This made tributes easier to pay, and also improved trade across the League, which improved the economic situation of a number of poleis. However, by destroying a nation’s national currency, Athens removed part of their culture and identity.

All League members had to follow Athenian law, which was often very different from the laws of other poleis in the League. League members had to travel to Athens in order to bring a case to court, which was very time-wasting and expensive. When League members did get to Athens, they had to face an all-Athenian jury, which would obviously be very biased in Athens’s favour. So, if a League member wanted to bring a case against Athens or an Athenian, they would find this incredibly difficult and victory would be very hard to gain.

One of Athens’s most controversial policies involved cleruchies. Cleruchies were settlements of Athenian people in the territory of one of the allies. The best land in the ally polis was taken from the natives to give to the Athenians in these settlements. This was good for Athenians, because they could live in different places and cultures that they would not have been able to experience without the cleruchies. They also got the best land from the polis they lived in, when they often would not have had good land (or sometimes any land at all) back in Athens. Of course, it was bad for the allies, because their best land was stolen, leading to many natives being displaced. Citizens of ally poleis would often fall into desperate poverty because they lost their homes and land.

Overall, Athens took a very harsh approach towards anyone who dared to rebel against their authority. This can be seen through their treatment of poleis such as Naxos and Thasos. It is also shown by considering Melos. Athens wanted Melos to join the Delian League, but Melos resisted. Melos was eventually defeated, and to punish them Athens decided to execute all the men in the polis, and sell all women and children into slavery. Melos then became a cleruchy for Athenians.

In what ways would Ancient Athens have been worse were it not for the Delian League?

What type of Ancient Greek people would have been more likely to support democracy? What type would be more likely to be against it?

Overall, do you think introducing Athenian coinage across the League was a good or bad thing?

Why would the Athenian poor have liked the idea of cleruchies?

Would the Athenians who didn’t move to cleruchies have benefitted from them? If so, how? You may wish to consider the amount of space and number of people in Athens.

Were the citizens of Melos treated fairly?

The main advantage Athens got from the Delian League was money – tributes from the Delian League made Athens extremely wealthy. This money was used to pay for jurors and maintain the legal system. It was used to pay for political officials such as archons and members of the Boule. It was used to maintain the Athenian navy and ensure it was in good condition. It was also used to maintain Athens and ensure it was a nice place to live. For example, the Parthenon was built using League funds.

Athens also had the power to punish poleis that it didn’t like such as Aegina. This must have been very satisfying for some Athenian citizens.

Cleruchies were good for Athens because they allowed the Athenian poor a better life. These people could get land of a quality they wouldn’t be able to get at home. They could also experience new cultures and lifestyles by migrating to a different polis.

Athens’s Empire clearly satisfied the ego of its citizens – Athens now had unrivalled power and wealth. It had a very capable military and lots of money and land.

However, there were also some disadvantages. Primarily, Athens had to protect its League members from threats like Persia. Many Athenian men died protecting other poleis that had nothing to do with them apart from the fact they were in the League. Athens also had to protect against revolts from within the League. This often led to the deaths of many Athenians. Keeping an eye on the allies by setting up garrisons required money and manpower.

On the other hand, the fact that Athenian forces experienced frequent battles ensured that they were very well-trained and battle-hardened. This was one of the reasons for Athens’s military might.

As Athens grew more powerful it became isolated from its neighbours, particularly those poleis which were members of the Delian League. This isolation eventually led to Athens’s downfall.

Why would isolation from the poleis around Athens lead to its downfall? Consider how much support it would have in a crisis.

Overall, was the Delian League advantageous to Athens? Why / Why not?

There were a few advantages of the Delian League for the allies. For example, they received Athenian protection from threats like Persia. However, this did mean that they never had a chance to improve their fighting ability by participating in battles – they became reliant on Athens and unable to protect themselves.

The fact that coinage was standardised throughout the League improved trade between ally poleis, because using the same money made payment a simpler process. This economically benefitted many League members. However, getting rid of the coinage previously used in League states lead to a loss of national identity, since the kind of money a polis used was part of its culture.

Many in the Delian League benefitted when Athens spread democracy. Previously, ally poleis were most likely tyrannies – only one person had all of the power. Therefore, introduction of democracy gave the citizens of poleis much more power than they had had before. On the other hand, there were likely a lot of people who didn’t like democracy, and for these people the introduction of democracy to their polis by Athens was a bad thing.

League members were disadvantaged because they were forced to pay tributes to Athens. This money mainly went towards improving life in Athens, and therefore didn’t really benefit League members. The tributes were often unfairly large, particularly for poleis like Aegina which Athens didn’t like.

League members faced very harsh punishments if they were seen to go against Athens in any way. For example, after Melos tried to rebel Athens killed all of its men and sold the women and children into slavery. Therefore, the people in allied poleis would have had to live in fear of these kinds of punishments.

It was humiliating for Greek states to be seen as under the control of anyone else. Therefore, being a member of the Delian League would have been very humiliating for the allies. They were faced with constant reminders of their subjugation in the form of garrisons that were positioned in some ally poleis.

League members had no control over foreign policy – they would go to war and fight with other states they had no quarrels with, just because Athens wanted them to. Some poleis that contributed ships had to sacrifice their time and even their lives in battles that had nothing to do with them.

Because many poleis in the League – such as Thasos and Naxos – weren’t allowed to have a navy, they had no independence. They had to rely on Athens completely for protection, and if Athens decided not to protect them they would become very vulnerable. Furthermore, they had to obey Athens completely, because Athens could defeat them very easily.

The legal system in the Delian League disadvantaged the allies. Allies had to travel to Athens to take a case to court, which was both time-consuming and expensive. For most people, this wasn’t an option. Furthermore, the few people who were able to get there had to face a jury made entirely of Athenian citizens, who would clearly be biased towards the Athenian citizen in any legal battle. Therefore, members of an allied state had very little chance of success in a legal battle with an Athenian.

Finally, cleruchies were very bad for the allies. Members of an allied polis had to give their land to Athenians, and were often forced into poverty because of this. Often the best land in the polis was given to Athenians, meaning that citizens of that polis could only settle for inferior land.

Overall, was the Delian League advantageous for the allies? Why / Why not?